No school until age seven: Finland's education lessons for the future

READ MORE

This Arctic Circle community might be the official home of Santa Claus, but according to Rovaniemi City Council’s Chairman, the best gift children in Finland receive each year is a free, world-class education.

“A great education builds better lives and a better world – it is this simple”, Heikki Autto says.

More than 10,000 of the city’s 62,000 residents are students and their right to education equality – at any age – is safeguarded in Finland’s Constitution.

School isn’t compulsory here until the age of seven – there are no national tests, no rankings, no inspections, no selective schools and very few private schools. For every 45 minutes of learning, students enjoy 15 minutes of play.

“Learning should be fun”, says Kristiina Volmari from the Finnish National Agency for Education. “We let children be children for as long as possible.”

The Finnish national curriculum is deliberately broad and focuses on individual improvement and advancement rather than collective assessment.

“We want our teachers to focus on learning, not testing. We do not, at all, believe in ranking students and ranking schools,” Ms Volmari says.

“In Finland, having happy children is the most important thing, we want to bring back the joy of learning. When you go to schools here, you see happy, active and engaged pupils.”

We do not, at all, believe in ranking students and ranking schools

Happiness is paramount but Finnish educators and innovators from the country’s booming tech industry think there’s something else to it: a system that encourages independence, creativity and a love of learning will be the recipe for success in a global future of technology and automation.

Does Finland still have the ‘best schools’?

Finland’s education system became the envy of the world for its top performance in the OECD’s international PISA tests over the past two decades, which rank countries by their students’ performance in literacy, maths, science and problem-solving as well as more subjective measures like life satisfaction.

This was always somewhat ironic, as the Finnish system is the anathema of a test-based education system.

Books like the influential Finnish education expert Pasi Sahlberg’s ‘Finnish Lessons 2.0: What Can The World Learn From Educational Change in Finland’, brought the tiny Nordic country’s education philosophy to a much larger audience.

But as more and more countries, particularly in East Asia, designed their curriculum around competency in the PISA tests, Finland’s performance slipped somewhat in the most recent PISA test in 2015, though it remained 12th ranked in the world.

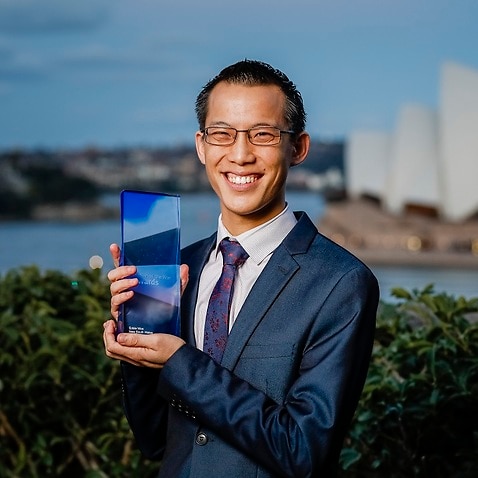

Professor Sahlberg, who this year joined the University of New South Wales’ Gonski Institute for Education, has outlined complex reasons that might be behind this, including a larger number of lower performing students, difference in how boys and girls lear, and austerity measures that have hit Finnish school staffing levels.

“Finland’s results have slipped because the boys spend time on and have interest in something other than school. Another reason may be that while most of the 34 OECD member countries [like Australia] have adjusted their education policies and designed school reforms with higher rankings in PISA in mind, Finland has done the opposite,” Professor Sahlberg told SBS News.

But despite this, in the 2015 PISA Finnish students still reported close to the highest level of life satisfaction out of participating countries, and the lowest level of schoolwork-related anxiety.

The role of parents and outdoor play

It might be 22 degrees below zero at Saarenpudas Kindergarten, but students here enjoy bursts of ‘outdoor play’ all year round, whatever the weather.

“Children learn by playing”, explains teacher Erika Stewart.“The child feels good and confident and this way they develop very good social skills. Children learn when they feel they are participating, involved and active.”

Even at this young age, students sit down with their parents and teachers to develop an Individual Education Plan.

“These plans are always based on a child’s strengths and interests”, Ms Stewart says. “We listen to the kids about what they’re interested in learning, what they enjoy.”

Finland’s Basic Education Act is just 24 pages and outlines the country’s broad educational goals.

It is up to individual schools and teachers to interpret how best to achieve them, based on a student’s individual needs.

We listen to the kids about what they’re interested in learning, what they enjoy

“This gives us great freedom, control and ownership as teachers,” says Erika Stewart.

Parents play an active role in helping develop their child’s confidence and autonomy.

Mums and dads of students attending Saarenpudas Kindergarten have drawn portraits of their children to hang above their lockers and coat racks, listing all the things they love and admire about their personality.

“These help, everyday, to reinforce self-confidence and highlight the individual – the things that make each student who learns here unique”, Ms Stewart says.

School lunches are also free in Finland, and today the five and six-year-old students are busy serving themselves warm spaghetti bolognese from the buffet.

“Children love to be given responsibility”, Stewart says. “Here, when we go out to play in the snow, we don’t put the children in their jackets – we wait until the children dress themselves, and then we go out and play together.”

“We try to let the children be independent and devise the play, decide what they want to do, and we as teachers help to facilitate those activities and how they will learn from them.”

Valuing teachers

“Trust” and “ownership” are words teachers, parents and politicians use again and again to describe Finland’s education system.

Authority is devolved to the teachers, says Kristiina Volmari from the Finnish National Agency for Education.

“Most of the decisions are made at a school and classroom level. Foreign visitors and politicians say ‘Wow, it’s amazing how much you trust the principals and the teachers’ but for us it is kind of obvious – the ideology is ‘train the teachers well and then let them be’, because they know best.”

Only around 10 per cent of applicants for teaching jobs are successful and almost all have Masters qualifications. Teaching jobs in Finland are highly competitive.

“Teachers in Finland are very proud of their profession – they own it,” Volmari says.

Lessons become more structured in secondary school, but the focus remains on individual learning in a team environment.

“It is very much ‘active learning’, not simply sitting at a desk for hours and hours reading, writing”, says Kristiina Volmari.

Standardised tests versus creativity

Linda Liukas, the Finnish creator of the best-selling ‘Hello Ruby’ books which introduce coding to young children via colourful characters, attributes her success to a school system that acknowledged her individual and creative style of learning.

Linda Liukas, the Finnish creator of the best-selling ‘Hello Ruby’ books which introduce coding to young children via colourful characters, attributes her success to a school system that acknowledged her individual and creative style of learning.

“Kids learn best when they are curious, fearless, inventive and allowed to make mistakes,” she says.

“Our future technological challenges won’t be solved by our current engineers. That’s why it’s important to take high, abstract concepts and make them at a level children can understand and engage with.”

The books have been printed in 24 languages and account for 20 per cent of Finland’s annual book exports.

During a recent trip to Australia, she was not impressed with the national assessment system NAPLAN.

“It just wouldn’t work in our system. Stressed kids are not learning and stressed teachers are not teaching.”

“I wish and I hope [Australia] provides more room for the teachers to do more of the stuff that teachers do best and remove a lot of the rote and mechanical assessments and grading papers. The system needs to be designed around this engage-based and playful way.”

“Computers are excellent at answering questions like ‘if this, then that’, whereas human kids and adults are good at asking, ‘what if?’. Hopefully our future schools will be more about ‘what if?’ and less about ‘if this, then that.’”

Education for innovation

While Finland’s focus on ‘happy students’ is altruistic, it’s also born from necessity.

“We are one of the most fastest ageing societies in Europe so instead of a population pyramid, we have a mushroom”, says Volmari from the Finnish National Agency for Education.

Today, the biggest sector is services, “And we believe the next sector for us will be innovation”, Volmari says.

Sanna Lukander should know. She set up the publishing arm of the Finnish games company (and ‘Angry Birds’ creator) Rovio Entertainment Corporation, and now runs her own business with a plan to ‘game-ify’ educational textbooks. Her Fun Academy has developed a successful learning program based on space exploration.

She believes countries with a strong emphasis on standardised tests and rote learning are wrong to focus on an education system that produces “robot students”.

“What are our educational objectives? Students who learn a curriculum and regurgitate information become compliant adults and are great for making armies,” she says.

“But do democracies like Australia and Finland want this?”

“Computers can do these sums much faster and more efficiently than any human ever will, but what they can’t do is replicate human emotions and creativity.”

“In this next generation the people who love to learn are the ones who are going to succeed in life.”

Article source: https://www.cinemablend.com/previews/1717670/the-1517-to-paris

Comments

Post a Comment